Handbook on Autism

by Cheryl Thacker

This Handbook is the outcome of a master’s project completed

by Cheryl Thacker at the University of Saskatchewan.

SSTA Research Centre Report #98-01:117

pages, $17

|

Table of Contents

Introduction

Chapter One - Literature Review

Chapter Two - Teaching Strategies and Techniques

Chapter Three - Case Study

References

Bibliography

Appendix A - Diagnostic Criteria

for Autistic Disorder

Appendix B - Diagnostic Criteria

for Asperger's Disorder

Appendix C - Diagnostic Criteria

for Mental Retardation

Appendix D - Schedules

Appendix E - Social Story for Taking

Turns at the Computer

Appendix F - Special Bibliography

Appendix G - Lesson Plan |

Overview

The Handbook on Autism includes:

-

a review of the literature and major influences in the field

of autism.

-

the aetiology of autism.

-

Asperger’s syndrome: considered to be at the higher end of

the autism continuum.

-

hyperlexia: a disorder in where very young children can read

exceptionally well, but often time without corresponding comprehension.

-

practical strategies: Strategies to use in the classroom

and home to increase and improve the social and communication skills of

people with autism.

-

a case study: The life story of a young boy with autism.

The field of autism has a definite, definable history, which

is dealt with in the Handbook. Researchers can not always agree as to what

causes the disorder known as autism, however, it has been proven quite

sufficiently that poor parenting does not cause autism.

This Handbook is intended to be used by parents, professionals,

and people with autism. It is hoped that this Handbook can help, in some

small way, parents, caregivers, and teachers to find some practical answers

to the puzzling condition known as autism. |

Introduction

There is no doubt in anyone's mind, at least those who work with children

and adults challenged by autism, that this particular group of people present

with puzzling, and often times, difficult behaviours. We do not yet know

the specific cause of autism, nor are there any reliable cures for autism.

We do know, however, that by employing various techniques and strategies

with people who have autism, we can reduce excessive behaviours and improve

deficit behaviours (Schriebman, 1994).

Chapter 1 will provide an overview of the disorder known as autism.

It will cover the current thoughts in the field, as well as look at the

history of autism. The aetiology of autism will be explored as well.

Chapter 1 will then focus on the issue of social skill development in

individuals with high-functioning autism. It will address the development

of play skills as well. Some of the current literature regarding social

skill development and play skills will be reviewed.

Chapter 1 will explore Asperger's syndrome. This section will focus

on the history and characteristics of children with Asperger's syndrome.

The phenomena of hyperlexia will also be examined.

The next section of Chapter 1 will focus on the relationship of autism

to mental retardation. Various viewpoints relating to this issue will be

explored. The final section of Chapter 1 will look at the literature regarding

behaviour modification techniques as applied to individuals with autism.

Chapter 2 deals specifically with the strategies and techniques. This

chapter begins by looking at techniques to increase and improve the social

and communication skills of individuals with Asperger's syndrome. Interventions,

such as integrated play groups and social reading strategies will be outlined,

as well as other strategies. Chapter 2 will end with a discussion of behaviour

modification techniques. Many times, the high-functioning individual with

autism engages in inappropriate or self-abusive behaviours. Therefore,

knowledge of basic behaviour modification techniques and principles is

essential for all those involved with individuals who are challenged by

autism.

Chapter 3 presents a case study of a young boy diagnosed with autism.

His past history, diagnosis, and current educational placements will be

outlined. In order for the reader to obtain a general idea of what life

is like for someone who has autism, his personal characteristics and idiosyncrasies

will be detailed,

This handbook in intended to be used by parents, professionals and people

with autism. It is hoped that this handbook can, in some small way help

parents, caregivers, and teachers to find some practical answers to the

puzzling phenomenon called autism.

Many people helped with the completion of this project. A warm and heartfelt

thank you is extended to everyone listed below.

I could not have even begun this project if it were not for my landlords,

who were also my children's caregivers. They looked after me and my children

and gave me the time I needed to study and write this handbook.

My college supervisor was a constant source of encouragement and support.

I learned so much from her. Even long distances did not prevent her from

"being there" for me.

I wish to thank my parents for helping with the children. We appreciated

all the free meals as well!

A special thank you goes out to Betty Fisher. Betty's contribution to

this project was invaluable. Thanks so much, Betty!

Many of the people on the list that follows were kind enough to share

with me their memories of, and stories about the autistic children and

young adults they have worked with over the years. Collecting the "stories"

was perhaps the most enjoyable part of the project for me - listening to

people reliving their happiest and saddest moments with individuals who

have autism reinforced for me that the autistic population is truly incredible

and amazing.

The illustrations found in the handbook were done by Frances Walsh.

Thank you, Frances, for the beautiful pictures.

I cannot possibly list everyone's contribution to this handbook. Therefore,

I will simply list everyone's name and say once more - Thank you very much.

| Jean Bacon |

Barb Bloom |

Wilma Clark |

| Loretta Eldstrom |

Betty Fisher |

Irene Friesen |

| Donald Gallo |

Bruce Gordon |

Velmarie Halyk |

| Connie Hawkemess |

Paulette Lavergne |

Wayne MacDonald |

| Orlene Martens |

Pom Matheos |

Corrie Melville |

| Cassie Olesko |

Bev Poncelet |

Eugene Schumacher |

| Ev Schumacher |

Gloria Stang |

Mary and Ted Thacker |

| Kathryn Whitby |

Gloria Woznik |

Frances Walsh |

And, of course, a big thank-you to "John" and his parents. Thank-you for

letting me enter your lives and for letting me get so close to your family.

I really appreciate all the time you gave to me and I will always remember

my year with "John"!

Back to Table of Contents

Chapter 1

A. is a thirteen year old girl with autism. One Christmas, she was the

Master of Ceremonies at her school's Christmas concert. She was all dressed

up for the occasion with a new pink dress and pair of shoes. The principal

was standing next to her on the stage. He accidentally stepped on her new

shoe, while A. was giving a narration of the Christmas story. A. turned

off the microphone, turned to the principal, looked him in the eye, and

said, "Jesus Christ! Would you get off my new pink shoe!" A. proceeded

to turn the microphone back on, turned towards the audience, and calmly

continued with the narration.

Literature Review

General Overview of Autism

Definitions

Autism is considered a subgroup of Pervasive Developmental

Disorder (P.D.D.). Autism is thought to be at the most severe end of the

P.D.D. continuum (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Characteristics

of a P.D.D. include an impairment of social interactions, impairment of

communication skills, both verbal and non-verbal and impairment of imaginary

play. Often associated with autism are other symptoms such as: stereotypical

and repetitive repertoires of restricted activities, delayed development

of intellectual skills, impaired comprehension skills, abnormal eating

and sleeping behaviours, inappropriate responses to sensory input, and

self-abusive behaviours. A more detailed list of criteria for diagnosing

autism can be found in Appendix A.

An interesting viewpoint was shared with the world when Clara Claiborne

Park (1982) wrote a book about the first eight years of her autistic daughter's

life. Park defines autism as:

All the autistic child's deficiencies could be seen converging in this

one: the deficiency which renders it unable or unwilling to put together

the primary building blocks of experience. It affects the senses, it affects

speech, it affects action, it affects emotion. The autistic child does

not move naturally from one sound to another, from one word to another,

from one idea to another, from one experience to another. (p. 267)

Back to Table of Contents

CHARACTERISTICS AND HISTORY

Kanner

Autism, by now, has come to be a familiar term in our society.

I believe this is partly due to the movies and other media that depict

such phenomena as

B. is a four year old boy with autism. B. will only eat chocolate

chip cookies. Occasionally, B.'s mom can slip in some extra ingredients,

such as bran, in order to provide a little extra nutrition. However, most

of the time, B. will not tolerate any extra ingredients and will refuse

to eat anything if he detects a new taste in the cookie.

the autistic 'savant' (e.g. the movie RainMan) and best

selling books that describe 'cures' for autism (e.g. Sound of a Miracle:

A Child's Triumph over Autism, Stehli, 1991). I am sure that

most educators could provide a definition or description of autism. However,

most definitions go back to the 'father' of autism, Dr. Leo Kanner. In

1943, Kanner described eleven patients and their behaviours and called

these behaviours "inborn autistic disturbances of affective contact" (p.

250). He was the first to propose that autism could be and should

be a separate diagnosis on its own and not a part of mental retardation

or schizophrenia. Kanner was also the first, it seems, to point out that

autism is present from birth and is, therefore, unlike schizophrenia, which

is an acquired syndrome (p. 242).

Some of the common characteristics that Kanner (1944) lists

as falling under the category of autism include an inability to relate

to people or objects properly, "extreme autistic aloneness" (p. 211), non-existent

or disabled language skills, and the obsessive desire for sameness in the

environment.

Kanner points out that the autistic children he had studied

looked quite normal and he felt they were of average or above-average intelligence

(p. 217). Kanner includes a brief summary of the parents of the children

he had studied and he states that they all appeared to be highly intelligent

although not particularly warm or overly emotional (p. 217). Kanner refrains

from making a

C. is a four year old boy with autism. He very often cries while watching

videos. He gets very sad and puts his head on the floor and weeps. He only

seems to cry when the videos do not have music in them.

a blatant connection at this time, but he does question the

causal relationship between the autistic behaviours and the seemingly cold

parenting styles of the parents of these same children (p. 217).

Rimland

Since Kanner's first descriptions and case studies, people have written

about autism from varying viewpoints. Most writers on the subject will

describe the behaviours and characteristics of autism, all of which resemble

Kanner's first descriptions very closely. Rimland (1964) wrote about autism

more than 30 years ago, and the symptoms he described then remain relevant

today. For example, Rimland's list of autistic characteristics included

such things as trouble with toilet training, abnormal eating patterns,

repetitive behaviours, stereotyped play with objects, insistence on the

same routines, suspicion of deafness and inappropriate speech and language.

Rimland also describes the development of specific skills at an early age,

such as early reading skills or exceptional fine motor skills.

Rimland (1964) writes of the exceptional memory skills of autistic children,

as demonstrated by their replicating their environment in order to maintain

sameness. He also observes that remarkable memory skills are demonstrated

when the individual with autism is able to repeat extraordinary things

often after only hearing it once.

Another characteristic described by Rimland (1964) is above-average

spatial abilities often demonstrated by individuals with autism. This is

most often demonstrated through the swift completion of puzzle tasks.

Rimland (1964) writes about the pronoun reversal commonly heard in the

speech of children with autism. Rimland offers an interesting explanation

for this pronoun reversal. He explains that the:

You-I reversal is clearly an example of what we refer to as closed-loop

phenomena. A sentence such as "Do you want some milk? enters the child's

hearing apparatus, is stored without being disassembled or analyzed, and

later emerges unchanged when an analogous stimulus situation arises. (p.

87)

Park (1982) also has an explanation for the pronoun reversal that is

so common among people with autism. Park feels that by explaining pronoun

usage to the autistic child one only makes the situation more confusing

for the child. Park wonders how any child learns the very complex skill

of pronoun usage in the preschool years. In her mind, normally developing

children and mentally retarded children use their social sense, which the

autistic child does not possess:

The social sense must take over and straighten things out - the sense,

or complex of senses, that assesses the relations of people in a given

situation, how they think of themselves, and consequently what words they

use to identify themselves...What it lacks is that social instinct which

guides even the dullest of normal children in the labyrinth of personal

relations. (p. 206 - 207)

Rimland (1964) describes the prognosis for autism, as it was seen in

1964, as being "closely linked to the speaking ability of the child" (p.

16). This is similar to more current ideas, which indicate that the more

speech an autistic child possesses, the better the prognosis (e.g. Frith,

1989).

D. is an eleven year old boy with autism. The staff at his school

can not leave any type of open containers in his view. D. will urinate

into any open container he sees, even a pop bottle, without making any

kind of mess whatsoever.

Apparently, researchers of autism in the 1960's, were disappointed by

the therapies available to children and parents. Rimland (1964) states

that "autism has not been influenced by any form of therapy" (p. 17). It

seems that families were given opposing advice during the 1950's and 60's.

Kanner was advising that "children raised in warm and affectionate surroundings

tend to do somewhat better...other writers have commented that autistic

children tend to do best in a rigid, minimally stimulating environment"

(Rimland, 1964, p. 17).

Rimland (1964) has studied the characteristics of parents who have children

with autism. Rimland cites case after case that describes either one parent,

or both, as very intelligent and capable. Rimland also found this group

of parents to be obsessive, particular to routines and attentive to details.

However, Rimland views these as positive characteristics, as opposed to

negative influences. He indicates that because these parents were so highly

intelligent, and persistent, they demonstrate much concern and caring for

their autistic children. This was in direct opposition to what Bettleheim

(1967) was saying, around the same time.

Bettelheim

Bettelheim (1967) describes classic symptoms of autism such as "sitting

motionless" (p. 98), mutism or echolalia, self-stimulating movements and

unnatural obsessions with objects (p.98). Bettelheim, unlike Kanner, does

outline definite ideas as to the cause of such autistic behaviours.

He states that "infantile autism is a state of mind that develops in

reaction to feeling oneself in an extreme situation, entirely without hope

(p. 68). He goes on to say "that the precipitating factor in infantile

autism is the parent's wish that his child should not exist" (p. 125).

Bettelheim feels that this rejection by the parents begins with poor breast-feeding

techniques that leaves the baby upset and unfulfilled and the mother feeling

rejected by the baby. This then snowballs into more and more unsatisfying

encounters between mother and child, until finally the baby turns away

from all interactions and begins his/her descent into autism (p. 395).

Bettelheim advocates the removal of these autistic children from their

homes. He himself, placed several children with autism in an institution

and used a combination of 'love' and psychotherapy to bring these children

out of their deeply depressed state. He claims to be very successful at

doing this. He reports that:

Altogether we have worked with forty-six autistic children,

all of whom showed marked improvement. But for purposes of comparison the

following remarks will be restricted to only forty of these forty-six because

one of them (Laurie) was withdrawn after a year; one, unbeknown to us when

we accepted her, had been subjected to a long series of electroshock treatments

a year before she came to us, which precluded effectiveness in our treatment

methods; and four others, at this writing, have not been with us long enough

to make valid assessments… there were eight in our forty for whom the end

results of therapy were "poor" because, despite improvement, they failed

to make the limited social adjustment needed for maintaining themselves

in society… seventeen children whose improvement we classified as "good"

can for all practical purposes be considered "cured"....The fifteen classified

as "fair...are no longer autistic, though eight of them should now be classified

as borderline or schizoid, since they have only made a fair social adjustment.

The remaining seven do much better and only suffer from more or less severe

personality disorders, which limitation has not kept them from making an

adequate social adjustment. (p. 413 - 415)

Rimland (1964) argues against the idea that autism is caused by a cold

and uncaring environment. Rimland strongly advocates for a biological cause

for autism. He sees the parents' unique characteristics as part of the

biological problem and not the cause of the problem.

Park (1982) comments, in her book about her autistic daughter, how it

was that some parents might have appeared cold and unfeeling to professionals.

She talks about meeting with professionals and being extremely disappointed

- Park and her husband were not treated as people, but as a "case". In

one instance with some professionals, Park remembers:

Refrigerator professionals create professional parents, if

the parents are strong enough to keep command of them-selves at all. I

had gone in a highly emotional state, ready to tremble, to weep, to dissolve

in gratitude. Received not even with reproaches, but with no reaction at

all, I of course dried up my emotions at once and met professionalism with

professionalism. (p. 143 - 144)

Nowadays, this idea of parental causation for autistic behaviours is considered

inappropriate and is no longer advocated by professionals in the field

(Kauffman, 1993, p. 212; Tsai & Ghaziuddin, 1992, p.53; Powell, Hecimovic

& Christensen, 1992, p. 191).

Delacato

In the 70's new approaches to dealing with autism appear. Prominent

among them was a sensory-integration type of treatment developed by Delacato

(1974). Delacato's research led him to believe that "These children were

not psychotic. They were brain-injured" (p. 54).

Delacato's (1974) treatment consists of first identifying the "sensoryisms"

(p. 84) of tactility, smell, vision, auditory and taste and then deciding

if the child was hyper or hypo in the sensory experience. The actual treatment

provides either extra stimulation or reduced stimulation to the affected

sensory organs. Delacato claims to have been successful in treating six

out of seven children discussed in his case studies. However, he does state

that "this theory is not presented as a 'cure-all'. Even with this theory

and these practices, I have failures" (p. 167).

Hinerman

More recent writers in the field of autism have been more consistent

when

it comes to describing the characteristics of autism. Hinerman (1983) has

done an excellent review of the various characteristics. She describes

the behavioural characteristics as "slow development or lack of physical,

social, and learning skills…abnormal responses to sensations…abnormal ways

of relating to people, objects and events" (p.5).

E. is a six year old boy with autism. E. is very agile and sure-footed.

E. is able to climb up onto the roof of his house and walk along the edge,

right beside the gutter, without falling off.

Autism is usually defined as involving language impairments as well,

which may include such things as "immature grammatical structure, delayed

or immediate echolalia, pronominal reversal...abnormal speech melody...poor

receptive language...mutism, or a kind of language that does not seem intended

for the purposes of interpersonal communication" (p. 7).

Another major area of dysfunction for the autistic person is the area

of social relationships. They may display a "lack of responsiveness to

people, lack of interest in people, failure to develop attachment to the

mother (as infants), lack of eye contact and facial responsiveness, and

indifference or aversion to affection and physical contact" (p. 8 -9).

Of course, some individuals with autism may display other characteristics

as well, which may include such things as "unusual responses to their environment...an

obsessive attachment to certain objects...aversion to clothing...self-stimulatory

behaviour...stereotyped play patterns...severe disturbances in the development

of perception" (p. 9).

Frith and Baron-Cohen

The prevailing theory in the field of autism today involves

a concept called the 'theory of mind' (Frith, 1989). This theory is very

useful in that it can explain

or give reasons for the apparently bizarre behaviour of many people with

autism. Frith describes theory of mind as a tool that people possess and

use when

F., age thirteen, is diagnosed as a high- functioning person with

autism. One day F. overheard his teacher discussing a book on autism with

another teacher. They were talking about a part of the book which quoted

an autistic child saying she could "hear" her own heartbeat and blood flowing

through her veins. F. turned, looked at his teacher, and asked, "Can't

everyone?"

dealing with others. It is a mental process we go through in our relationships

with other people. It allows us to infer what other people are feeling

and thinking, and lets us predict what may happen next.

Baron-Cohen (1995) defines theory of mind as the ability "to

attribute mental state to oneself and to others and to interpret behavior

in terms of mental states... mental states are unobservable entities that

we use quite successfully to explain and predict behavior" (p. 55)

Frith (1989) proposes that people with autism lack this theory of mind:

The possibility that autistic children lack a theory of mind has been

suggested already on the basis of their peculiar inability to relate to

people in the ordinary way. One implication of this hypothesis is that

autistic individuals are natural behaviorists and do not feel the normal

compulsion to weave together mind behavior for the sake of coherence. (p.

158)

G. is a twelve year old girl with autism. G. can say a few words,

but relies on sign language for the bulk of her communication needs. G.

can finger spell exceptionally well. She watches the learning channel on

TV and has come to school finger spelling such complicated words as "archaeology"

and "Smithsonian".

Baron-Cohen (1995) explains that in order for people to have

a theory of mind mechanism (ToMM), they must also have a shared attention

mechanism (SAM). Baron-Cohen says the shared attention mechanism (SAM)

happens when two people focus their attention on the same object. The SAM

uses "available information about the perceptual state of another person

(or animal)… It then computes shared attentions by comparing another agent's

perceptual state with the self's current perceptual state (p. 45 -46).

Frith (1989) goes on to explain that the "loneliness of the autistic

child does not merely consist of a deficiency in expressing and understanding

emotions. To the autistic individual other mental states, such as knowing

and believing, are equally a mystery" (p. 168).

Frith's (1989) arguments leading to these conclusions are lengthy and

detailed. She compared normally developing children, mentally handicapped

children and autistic children. Her experiments showed that normally developing

children and mentally handicapped children, although different in IQ, could

both identify mental states in others. Because these children had a knowledge

of how the human mind works, they could predict other's behaviours. This

was not the case, however, for autistic children.

Baron-Cohen (1995) and associates have also shown through similar experiments,

that autistic people do not possess a SAM or a ToMM. However, they have

shown that young children and children with intellectual disabilities do

possess both mechanisms. This supports the theory that the basic deficit

of autistic people is their lack of theory of mind.

The theory of mind concept has implications for how we can deal with

individuals with autism. Frith (1989) explains:

H. is a young three year old boy with autism, who cannot talk. H.

has some peculiar eating habits. He will only eat one food at a time, for

days or weeks on end. For example, sometimes H. will only eat potato chips

for one week, then suddenly, for no apparent reason, he will switch to

eating only cookies for a week, and so on.

it would be useful to adopt a literal and behaviorist mode

as a partner of an autistic person, both as listener and as speaker. Implications

need to be spelled out for the autistic person, even if they seem redundant

and self-evident in normal communication....information needs to be actively

solicited since the autistic person may 'forget' to mention an important

fact. (p.180)

Baron-Cohen (1995) discusses ToMM and its relationship to language development.

Baron-Cohen questions which develops first - language or the ability to

read another person's mind? Baron-Cohen argues:

that this drive to inform, to exchange information, to persuade, or

to find out about the other person's thoughts is principally based on mindreading,

and that mindreading is enabled by the language faculty. But by itself,

unless it is hooked up to the mindreading system, the language faculty

may hardly be used - at least, not socially. (p. 131)

Baron-Cohen (1995) feels that we are mindreaders first, then developers

of language. He defines mindreading as the "capacity to imagine or represent

states of mind that we or others might hold" (p. 2). Baron-Cohen supports

his argument that this mindreading ability develops before language by

stating:

consider a person who has an intact language faculty but who cannot mindread

(autism arguably being such a case). Such a person would be able to reply

in perfectly well formed sentences when asked a question like "Where do

you live?" but would be unable to engage in social dialogue - normal conversation.

(p. 131)

Baron-Cohen (1995) stresses that there are many types of autism

and other subgroups many involve more than what he calls "mindblindness"

(p. 1). Mindblindness is being aware of the physical world, but unaware

of mental things; "blind to things like thought, beliefs, knowledge, desires,

and intentions" (p.1). Baron-Cohen suggests that "we need to be careful

about concluding that autism involves mindblindness and nothing else. My

suggestion here is that autism involves mindblindness as a core deficit,

but that other deficits may co-occur" (p. 137).

Aarons and Gittens

Historically, the diagnosis of autism has been problematic. At one time,

researchers and others in the field diagnosed autism on the basis of "all

or nothing" (Aarons & Gittens, 1992, p. 23). Most people in the field

are now moving away from this towards looking at the characteristics on

the

continuum of autism. Aarons and Gittens recommend a "descriptive approach

to diagnosis" (p.23) that includes "observation of children in a social

setting, such as a school or nursery, where their difficulties are more

likely to be highlighted among normal functioning peers" (p. 24).

Another problem with accurate diagnosis of autism is that often the

behavioural troubles exhibited by the child may be attributed to poor parenting.

According to Aarons and Gittens (1992) the problems:

are seen as the outcome of a breakdown in family dynamics,

rather than symptomatic of an underlying disorder. This misinterpretation

of the causes of the child's presenting behavior has brought considerable

distress to many parents who feel that they are being blamed undeservedly

for their child's problems. Yet they are unable to find an alternative

explanation which would make better sense. (p. 25)

What, then, can be done to accurately and consistently diagnose and separate

autism from other handicapping conditions? Aarons and Gittens (1992) offer

a model for diagnosis that includes "looking at the whole child and evaluating

his/her individual difficulties as well as possible abilities and skills"

(p. 30). These authors suggest that professionals in the field look at

several broad areas such as, medical history, early development, appearance,

movement, attention control, sensory function, play skills, basic concept

development, sequencing skills and musical skills.

Back to Table of Contents

AETIOLOGY

Frith (1989) is very firm in her belief that autism, "undoubtedly...has

a biological cause and is the consequence of organic dysfunction" (p. 68).

Sacks (1995) is also a firm believer in a biological cause for autism.

Sacks, a neurologist, has speculated that the aetiology may be genetic

in some cases. Autism may also be associated "in the affected individual

or the family, with other genetic disorders, such as dyslexia, attention

deficit disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, or Tourette's syndrome"

(Sacks, 1995, p. 248).

Autism may also be acquired. For example, a number of babies exposed

to the rubella virus during the 1960's later developed autism. They began

to develop normally, then suddenly lost both language and social skills

between the ages of two to four (Sacks, 1995).

Autism could also be caused by a metabolic disorder such as phenylketonuria

(PKU), or a "mechanical" (Sacks, 1995, p. 248) disorder such as hydrocephalus.

Temple Grandin, a person with autism, spoke to Oliver Sacks (1995) about

her thoughts regarding the aetiology of autism. Grandin believes that parts

of her brain are highly developed and are very productive, for example,

the part that controls visualisation. She believes that other parts of

her brain are poorly developed, such as the part that controls verbalisation.

Grandin believes this to be true for most people with autism:

she ascribes this to a defect in her cerebellum, the fact that (as an

MRI has shown) it is below normal size in her. She believes such cerebellar

defects are significant in autism, though scientific opinion is divided

on this. (Sacks, 1995, p. 289)

Grandin questions Frith's (1989) theory of mind as a causal explanation

for autism. Grandin herself:

faces , almost everyday, extreme variations, from over-response to nonresponse,

in her own sensory system, which cannot be explained, she feels, in terms

of "theory of mind." She herself was already asocial at the age of six

months and stiffened in her mother's arms at this time, and such reactions,

common in autism, she also finds inexplicable in terms of theory of mind.

(Sacks, 1995, p. 290 - 291)

Kauffman (1993) notes in his review of the literature, that "autism…is

known to involve a dysfunction of the central nervous system, but the nature

of the dysfunction, remains unknown (p. 181). Tsai and Ghaziuddin (1992)

outline several possible causes of autism, including genetic factors, obstetric

and postnatal factors, neurological factors, and immunological factors.

Although there seems to be no consensus as to one single cause or aetiology

for autism, one thing is clear from the research: "autism is a heterogeneous

behavioral disorder with several different but distinct subtypes" (Tsai

& Ghaziuddin, 1992, p. 67).

J. is a four year old boy with autism. J. can identify his parent's

friends, not by name, but by licence plate number, car make and colour.

J. will approach an adult friend of his parents and simply begin listing

vehicle characteristics - make, model, colour, and plate number, without

prefacing the conversation with a "hello" or "hi". H. is always correct

when matching vehicles to people. J. otherwise does not possess any meaningful

social or communicative speech.

Social Interactions and Impairments

Definitions

Social skills and behaviours can be defined as "the ability

to communicate effectively with people in social and work situations" (Gordon

& Lawton, 1984, p. 179). Social competence can be thought of as "the

progressive capacity for looking after oneself which leads to ultimate

independence as an adult" (Van Osdol, 1972, p. 35).

Lorna Wing defines autism as being a "triad of impairments of social

interaction, communication, and imagination, together with a marked preference

for a rigid, repetitive pattern of activities" (Wing, 1992, p. 129). Wing

further describes the social interaction impairment as having three sub-categories.

One type of social impairment involves children who do not seem interested

in other people at all. They may accept food and drink from people in their

environment, but seem not to view the person as a person, but merely as

a tool for receiving basic need requirements. They are often described

as aloof.

A second type of social impairment that some autistic children may have

is described by Wing as being "socially passive" (Wing, 1992, p. 132).

Children with this type of impairment do not usually initiate social interactions,

but may respond when others do the initiating. They may also copy other

children's movements and behaviours without really understanding the reasons

for the behaviours in the first place.

A third type of social impairment involving children with autism are

those who may initiate interactions with others, but these interactions

are usually bizarre and nonsensical. These children may only talk about

a particular subject or repeat phrases over and over. They may be considered

odd by others.

Characteristics

Children with autism may display any of these characteristics

in different situations. Generally, however, by the age of five or six,

a child with autism will show more tendencies toward one of the subcategories

of social impairments than another.

Children with high-functioning autism also display these characteristics

of social impairments. Usually, such children display characteristics from

the passive or odd subcategories rather than from the aloof category. It

should be noted that children with autism neither lack the ability

to feel emotions nor do they lack the desire to interact with others.

It seems to be more a problem of "an overwhelming difficulty in acquiring

and understanding the multitudinous rules of social life and developing

empathy with others" (Wing, 1992, p. 131).

Children with autism view social interactions differently because of

their trouble understanding social rules and expectations. Some researchers

in this

K. is an eight year old boy with autism. He remembered the order

of presentation of a psychological test given one year previously. He could

remember the order of the subtests he was previously given by a different

psychologist. He told his current psychologist that she was not proceeding

in the correct order when she gave him the same test, but in a slightly

different order.

field feel that children with autism interpret each social interaction

separately. They can not generalise from one situation to another similar

situation. The children are often "left with a series of fragmented social

experiences that are manifested as ritualized, context-specific behaviors"

(Quill, 1995, p. 167). The goal of any treatment program, therefore, is

to make "social interactions more predictable and better understood" (p.

163).

School Problems

High-functioning children with autism encounter problems in

school settings that differ from those who are not high-functioning. Because

of their near-average, average, or superior intelligence levels, they may

not receive many special services in a school setting. These children may

be left on their own to cope the best they can with the complex social

expectations demanded in a school environment. They may have trouble attending

to tasks and may perseverate on their own obsessions during class time.

They may be ridiculed by classmates because of their odd behaviours and

mannerisms. Some high-functioning autistic children, however, have special

interests or obsessions that can lead to relatively successful interactions.

For example, some autistic children excel in music or chess or math games.

These skills can be utilised by school personnel to facilitate appropriate

social interactions (Wing, 1992).

The Normal Development of Play

Why Play is Important

The ability to play promotes social skill growth, among other

things, for young children. Play is fun for most children, but more importantly,

it is how they learn. While engaging in a variety of play situations, children

learn how to solve problems, fine tune their fine and gross motor skills,

learn communication skills and a diversity of social behaviours (Stone

& La Greca, 1986, p. 37).

It is important to know how typical children develop play skills and

how they interact with peers during play periods (Stone & La Greca,

1986, p. 36). This information can be used to compare how children with

autism differ from typical children in this area and "to provide a framework

of normally occurring social skills that could then be utilized in intervention

efforts with autistic children" (p.36).

Vygotsky, a Russian psychologist of the 1920's and 30's, clearly felt

that through play, children develop many skills, including:

the creation of voluntary intentions, and the formation of real-life

plans and volitional motives - all appear in play and make it the highest

level of pre-school development...in this sense can play be considered

a leading activity that determines the child's development. (Cole, et al.,

1978, p.102 -103)

Vygotsky (Cole, et al., 1978) demonstrates that learning does occur

during play by applying his zone of proximal development concept. He states

that in play a child is always operating at a level above his chronological

age. In play, Vygotsky observes, a child acts out skills beyond his everyday,

routine skills. This states Vygotsky, was when learning took place.

L. is a two year old boy with autism. Right now L. is very attached

to a jar of marbles. He takes them everywhere, and has never put a marble

into his mouth. The "object" L. is attached to changes from time to time,

however, he has something beside him at all times. L. even takes his special

"object" to bed with him every night.

Initial Play Development

During a child's first year of life, the purpose of play is

to develop

knowledge about self and significant others in the child's environment.

From birth to around age six months, infants are typically passive interactants

in the play process. They may show appreciation towards the play activities

initiated by parents or others in their environment by smiling and cooing;

however, they do not usually initiate the activities themselves. From age

six months to one year, babies will begin to share interests with familiar

people in their surroundings. They may initiate familiar play routines,

smile and coo to get attention and tentatively begin the sharing process

with toys (Wolfberg, 1995, Stone & La Greca, 1986).

An interesting study done by Lee in 1973 (as cited in Stone

& La Greca, 1986) looked at peer preferences of very young children.

Lee studied infants and toddlers between the ages of eight to ten months

old. He observed them in their typical day-care interactions and he compared:

one infant who was consistently approached by others...to a child who

was avoided. The preferred infant was observed to be more responsive to

social contacts and engaged in more reciprocal interactions with the other

infants. Thus, even at very early ages, the behavioral dimensions of "responsiveness

to others" and "reciprocity" in social interactions appear to be important

indicators of a child's likability. (p. 38)

Pretend Play

Starting around a child's first birthday, pretend play begins

to emerge. Pretend play is the ability to imitate adult behaviours in different

contexts (Wallach & Miller, 1988). Between the ages of one and four,

a child will play "mommy" or "daddy" or imitate the play behaviours of

older siblings and other children. Children at this stage spend time watching

how other children play, imitate the actions of other children and engage

in parallel play with other children (Wolfberg, 1995).

There are several social behaviours that develop in the preschool years

that facilitate positive play interactions between children. Some of these

positive behaviours include such things as "the frequency of smiling and

laughing… sharing and co-operative acts....good eye contact and physical

proximity" (Stone & La Greca, 1986, p. 39).

Co-operative Play

Gradually, co-operative play begins to develop, usually around

the age of four. Co-operative play, that is, sustained play between two

or more children, is a complex process. Children must understand the concept

of taking on different roles; they must adapt their movements and voices

to fit the play situation; and they have to be able to talk about how to

play with each other. As well, children must understand rules regarding

turn-taking. For example, children will typically give each other directions

about what action will happen or when to change play scenarios altogether.

These complex interactions can be thought of as "metaplay" (Wallach &

Miller, 1988, p. 19).

Older Children at Play

Vygoysky (Cole, et., 1978) feels that the nature of

play changes over time. Play starts out as a mere representation of real

life. The young child

M. is a boy with autism who is an escape artist. M. is ten years

old and is non-verbal. On the second day of school, he disappeared from

the school yard during a physical education class. School personnel looked

all over the school grounds and building, but when M. was not found, the

police were called. M. was found downtown, approximately ten kilometres

from the school. He was found by the security guards at a large department

store, in the TV section. No one is sure how M. crossed the streets safely

on his own, as this is not a skill he has successfully demonstrated before.

simply remembers a sequence of events and acts them out. Then play begins

to become more abstract; the child is able to separate the meaning from

the object. Vygotsky felt that play was not as serious for the school-age

child, primarily because school occupies so much of his/her time. However,

others do not agree with this sentiment. According to Wolfberg (1995):

games and sports are the dominant play activities formally

available to children in school and recreation programs while occasions

for make-believe play activities are rare. Nevertheless, the impulse to

pretend in middle childhood continues, particularly when opportunities

for imaginative activities are made available. (p. 200)

Children in elementary school display quite sophisticated play skills.

The sharing and co-operation skills that they learned in early childhood

continue to develop and are important for successful peer relationships.

Children at this age also become more responsive to their play partner's

needs and are more likely to change the play situation to suit their partner's

desires than younger children (Stone & La Greca, 1986, p. 41). School-age

children also learn some new play and social skills such as how to "enter

ongoing peer activities and to extend invitations to peers" (p.41).

According to Vygotsky (Cole, et al., 1978), play changes again, as the

child reaches adolescence. The more mature play of an adolescent helps

to develop abstract thought; ideas and concepts that had not been considered

important before now become dominant.

Many researchers agree that play contains several components that can

be found in various play situations and across age groups (Wolfberg, 1995).

These characteristics include the descriptions that: "Play is pleasurable....Play

involves active engagement in a freely chosen activity....Play is

intrinsically

motivated....Play includes flexibility....Play frequently has

a nonliteral or 'as if' quality" (p. 196).

Autism and the Development of Play

Characteristics

Children with autism have much different play routines and

play

characteristics as compared with the descriptions of typical children's

play

(Stone & La Greca, 1986). All children with autism are different and

each child will display his or her own individual play habits, (or lack

of play habits). There are, however, some common features of the play of

children with autism that can be described. Wolfberg (1995) has researched

the literature and summarises the characteristics in this way:

Overall, they lack the spontaneous and flexible qualities characteristic

of play....When left to their own devices, they commonly impose rigid and

perseverative play routines....Once established, many children with autism

express considerable resistance to a play routine being disrupted....they

tend to exhibit less time and diversity in advanced play skills, fewer

functional play sequences, and fewer symbolic play acts related to dolls

and others....Language, gestures, and sound effects that are indicative

of imagination are rarely spontaneously incorporated… they may repeatedly

construct and reconstruct the same intricate layout of buildings and roadways

but never actually incorporate novel elements into the construction....children

with autism tend to remain on the fringes of peer groups. (p. 201 - 203)

N. is a two year old boy with autism. N. is always full of energy

and loves to climb anything and everything. One day, when his mother had

a visitor in the house, N. climbed to the top of the wall unit, which was

bolted to the wall, and watched the visit from the top shelf.

Children with autism do occasionally attempt to interact with

peers; however, "the limited contact they have is generally negative in

nature" (Stone & La Greca, 1986, p. 46). The reasons for this may be

found in our current understanding of normal social skills development.

Skills such as "mutual visual regard, mutual object manipulation, and imitation"

(Stone & LaGreca, 1986, p.46), which are needed in order to play successfully

with others, begin to develop in very young children. Other skills that

facilitate successful peer

interactions are establishing and maintaining eye contact and playing in

close physical proximity to other children. Children with autism seem to

lack these skills right from the beginning of life.

Symbolic Play

In 1993, Jarrold, Boucher and Smith reviewed the current research

into the symbolic play of autistic children. They found several problems

with the research. The first problem they discussed concerned terminology.

It seems that different researchers use different terms. This makes it

unclear whether each researcher is actually studying the same phenomena

and confuses the issue when conclusions are drawn by comparisons between

studies.

Another problem that Jarrold et al. (1993) found was methodological

in nature. The authors concluded from their review that many researchers

failed to "include control groups or to match control groups adequately"

(p. 295). The authors stated that these shortcomings lead to limitations

in drawing conclusions about "any relative impairment in the symbolic

play of autistic children" (p. 284).

The authors did not dwell only on the negative aspects of the research.

They outlined some firm conclusions that can be found in the research as

well. They stated that the research appeared to point to the fact that

all types of play was impaired in similar ways in autistic children. That

is, autistic children do not typically excel at one type of play over another

type of play. They also concluded from the review that the play of autistic

children seemed to be impaired in all play situations.

Jarrold et al. (1993) concluded their review by discussing the uneven

language abilities characteristic of autistic children and the effect this

may have on studies into play. The authors cautioned that "careful consideration

must be given to the methods used to control for the effects of language

ability" (p. 303).

Normal Language and Communication Development

The Importance of Language

It is often difficult to separate communication skills from

social and play skills. The development and emergence of one affects the

development and emergence of all others. In fact, "communication has been

cited as the foundation of social interaction"

(Stone & La Greca, 1986, p. 47). As in the development of play skills,

it is important to look at the development of communication in typical

children. Then, the language development of autistic children, (or lack

of development) can be looked at in relation to social skill development.

Social Language

The unfolding of a human creature is a truly wondrous event, especially

when one looks at language development. Young infants and toddlers not

only learn and use the semantically, morphologically, and syntactically

correct aspects of language, but they must also:

learn the complex rules of the appropriate social use of language,

what certain scholars have called communicative competence. These rules

include, for example, the greetings that are to be used, the "taboo" words,

the polite forms of address, the various styles that are appropriate to

different situations, and so forth. (Fromkin & Rodman, 1993, p.394)

O. is an eleven year old girl with autism, who seldom talks. Se likes

to work behind a divider at school, so that no one can see her. One day,

while behind a divider, her teacher yawned. The teacher knew no one had

seen her do this, and that O. was hidden from view behind the divider.

However, O. apparently heard the yawn and commented through the divider,

"You tired, teacher?"

One of the first things that a baby learns about language is

how to get the attention of a significant adult in his/her environment.

It has been found that "by the age of 9 to 10 months, infants...initiate

communication through eye contact, physical gestures, and vocalisations"

(Stone & La Greca, 1986, p. 48). From the ages of two to three, the

child's oral language skills increase dramatically. However, the young

child still prefers to use gestures and eye contact as the predominant

means of initiating communication (p. 48).

Preschool Language

As the child enters toddlerhood, many new communication skills

emerge. For example, it has been found that preschoolers will "adapt their

speech in response to listener feedback as well as to specific personal

characteristics (e.g., age, cognitive level, linguistic level) of listeners"

(Stone & La Greca, 1986, p. 50). Preschoolers will also adapt their

responses to feedback from listeners; will ask relevant questions; and

will use language to organise play activities.

School-age Children

School-age children develop and refine their existing communication

skills, as well as develop more sophisticated skills. School-age children

become more effective at using and 'reading' nonverbal communications.

They also are better at both speaking and listening in general; they "become

more adept at eliciting attention and feedback from listeners, and are

able to respond appropriately to explicit verbal feedback (such as questions)

and adapt their speech to the listener's needs" (Stone & La Greca,

1986, p. 52).

School-age children also use their language and communication skills for

reasons that differ from younger children. Children at this stage use language

to initiate play acts, to resolve conflicts, and as an activity in itself;

"social activity becomes important in its own right as a shared peer activity"

(Stone & La Greca, 1986, p. 52).

Autism and the Development of Communication Skills

P. is a nineteen year old young man with autism. When upset, P. will

yell "Call 911 - call 911!", as he did one day in a grocery store when

he temporarily lost sight of his mother. On another occasion, P. was with

his class from school, on a hayride in the country. The driver of the wagon

was driving dangerously fast across the bumpy fields, causing everyone

on the wagon to be bounced around and all were somewhat frightened. P.

kept yelling over and over again, "Call 911 - call 911", until the hayride

ended.

Just as children with autism differ from other children

in many aspects of development, so do they differ in language and communication

skills. Children with autism "are typically late beginning to speak, and

approximately half never develop meaningful speech at all. Those who do

often demonstrate abnormalities in usage as well as delivery" (Stone &

La Greca, 1986, p. 53).

We know that infants and toddlers actively seek attention of others

through the use of eye contact and gestures. However, children with autism

usually fail to develop either of these behaviours, which then leaves them

at risk for not developing higher order skills. For those people with autism

that do develop speech and language, it is often non-communicative in nature.

That is, "conversation is often restricted to the use of stereotyped phrases

and the exchange of concrete pieces of information about limited topics

of interest" (Stone & La Greca, 1986, p. 53).

One can see from the literature regarding language and communication

development, that autistic children's impairment in these areas lead to,

and are undoubtedly connected to, their impairments in other areas such

as social skills and play skills.

Asperger's Syndrome

Hans Asperger was an Austrian psychiatrist, who first described

the condition we now know as Asperger's syndrome (AS) in a 1943 thesis.

Asperger used the term "autism" to describe his patients. This was the

same year that Kanner published his landmark article using the same term.

Asperger's work, however, remained unpublished until 1944, and untranslated

for some time after that. Asperger's work has only become prominent in

the last few years.

Definition

Frith (1991) defines Asperger's syndrome (AS) being made up

of people who:

tend to speak fluently by the time they are five, even if their

language development was slow to begin with, and even if it is noticeably

odd in its use for communication...often become quite interested in other

people and thus belie the stereotype of the aloof and withdrawn child....remain

socially inept in their approaches and interactions. (p. 3 - 4)

Frith (1991) describes people with AS in the following ways: many adults

with AS can function quite well as far as independent living and careers

are concerned. However, they often appear different and awkward. Obsessions

may dominate their lives and topics of conversation. They may appear blunt,

robot-like or cold-hearted. They may engage in stereotypical behaviours

when experiencing stress, similar to lower-functioning people with autism.

People with AS have reported strange sensory reactions, such as hypo- or

hyper- sensitivity to sounds or to the texture of clothes. AS is now included

in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders - 4th

ed (1994). It is called Asperger's Disorder and includes the diagnostic

features of "severe and sustained impairment in social interaction...the

development of restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests and

activities" (p. 75). Also included as characteristics of the disorder are

delayed motor development and clumsiness. The Manual states that the disorder

seems to be more common in boys and than in girls and usually has " a somewhat

later onset than Autistic Disorder, or at least to be recognized somewhat

later" (p. 76). A more detailed description of the diagnostic criteria

used in the Manual can be found in Appendix B.

The term 'high-functioning' is often used in conjunction with AS. There

is confusion in the literature regarding the use of these two terms and

exactly what is meant by each. Szatmari, Bartolucci, & Bremner (1989)

suggest that there is no difference between the two terms. They state that

there are some differences between the two populations "in terms of social

responsiveness, communication and restricted range of activities" (p. 717),

but these differences likely "reflect severity of the disorder rather than

a distinct disorder" (p 717). The authors go on to say that "it may be

best to think of AS as a mild form of HFA [high

functioning autism]" (p.717). For the purposes of this handbook, the

terms Asperger's syndrome (AS) and high functioning autism will used interchangeably.

High-functioning autism, or AS, usually refers to children with autism

who have an IQ score over 70; this "covers close to 20% of the autistic

population" (Levy, 1988, p.2). Frith (1991) considers AS a subcategory

of autism. She sees it as being on the same continuum as autism. Szatmari,

Bremner, & Nagy (1989) hold a similar view, that AS is "on the autistic

spectrum" (p. 559). These authors suggest that AS and autism "share a common

aetiology but differ primarily on severity" (p. 554). Frith (1989) states

that AS should "be reserved for the rare intelligent and highly verbal,

near-normal autistic child" (p. 8).

Characteristics

Some of the characteristics

of the condition, taken from Asperger's own working files, and still considered

in diagnosis today, are such things as:

-

the condition being more common in boys than girls,

-

being not identified in infancy, but usually after age 3,

-

walking may be delayed,

-

speech may occur at normal developmental age, with proper grammar eventually

developing, however, there may likely be evidence of pronoun reversals,

-

language tending not to be used for communication purposes,

-

having limited gestures and limited facial expressions, and limited understanding

of others' gestures and facial expression,

-

possessing abnormal vocal intonation,

-

lacking in understanding of social rules and behaviours,

-

having clumsy and uncoordinated movements, which may affect printing and

drawing skills,

-

may have good rote memory abilities,

-

may develop an obsessive interest in one or two topics,

-

may be teased because of eccentricities,

-

may become aware that they are different than other people and may seek

ways to become more normal-like (Frith, 1991).

Q. is a four year old boy with Asperger's syndrome. One day he was

playing with a small mirror at school. He wanted his teacher to look at

the little telephone in the mirror. The teacher could not understand where

this telephone was, but Q. insisted that it was in the mirror. Finally,

the teacher figured it out. There was a small telephone sticker on the

ceiling above them which the teacher had not noticed before, but obviously,

Q. had. Q. then turned the mirror over to the magnification side and told

his teacher to now look at the big telephone. Q. kept flipping the mirror

from one side to the other and was quite excited about the telephone that

changed size.

Since Asperger's work has come to be known, others in the field

(Wing, 1981; Levy, 1988) have added to the list of distinguishing characteristics

of people with AS. These characteristics include such things as:

-

reduction or complete absence of babbling in infancy and reduction of gestures,

smiles and laughter in early childhood,

-

may not have shown or shared toys with parents and significant others in

environment,

-

lack of ability to engage in pretend play with peers,

-

if play skills do exist, they may lack creativity and flexibility,

-

may relate appropriately with parents and other adults, but not with peers,

-

exhibits a large vocabulary; may know the meanings of difficult and obscure

words, while not comprehending common, everyday words,

-

difficulty with descriptive language and conversational turn-taking,

-

may ask repetitive questions with little concern about the actual answers

to the questions,

-

very concrete and literal, "seldom use colloquialisms, such as 'yea' for

'yes' or idioms, such as 'beating around the bush' " (Levy, 1988, p.4),

-

often display uneven academic skills,

-

lacks common sense,

-

many can be employed successfully in adulthood,

-

may be at risk for psychiatric illnesses in adulthood,

-

may be super-sensitive to criticism by others.

There are certain characteristics of the children that Asperger

described that differ from Kanner's descriptions of children he labelled

as autistic. Asperger described children who developed speech and language

by the time they entered school. They typically had large vocabularies

and demonstrated good grammatical skills. They tended to seek the company

of peers, but did not know how to do so appropriately. Asperger also described

these children as having original thoughts and strange

obsessions (Frith, 1991, p. 96 -97). In contrast, Kanner (1943, 1944) described

children who typically did not speak or, if they did speak, they possessed

a limited vocabulary. And, of course, the children that Kanner described

did not seek the company of peers; in fact they were characterised by "an

extreme autistic aloneness that, whenever possible, disregards, ignores,

shuts out anything that comes to the child from the outside (Kanner, 1943,

p. 242).

Grandin (1995), herself an individual with AS, has described some common

characteristics that people with her condition share. She stated that they

"tend to be good at visual thinking" (p. 47) and may be consumed with anxiety

and nervousness much of the time. Grandin said that the "anxiety felt like

a constant state of stage fright, and caused me to resist changes in routine

because changes made me more anxious" (p. 48).

McLennan, Lord and Schopler (1993) studied a small group of high-functioning

people with autism to see of there were any differences of behaviours between

males and females. Predictably, because of similar studies of other populations,

they found that the males were more handicapped than the females, at the

younger age level. Specifically, the younger females McLennan

R. is a non-verbal, two year old boy with autism. He is an accomplished

escape artist. One night he piled up an assortment of objects, undid the

latch at the top of his bedroom door, and ran away. The police found him

on a busy street in the neighbourhood.

et al. studied were better able to communicate effectively and better

able to initiate social interactions than were the males. This trend was

reversed, however, for older subjects; the males were seen as better communicators

in adolescence and young adulthood. The authors offer a reason for this.

They speculate that the adolescent autistic girl who wants to interact

with her normal peers must typically have good communication and interaction

skills. (Normally developing teenage girls' social experiences consists

of talking and other social interactions.) The autistic girl's weaknesses

are highlighted during these encounters. However, adolescent boys' interactions

tend to revolve around playing sports or watching sports on TV, etc. The

autistic teenage boy does not need as refined communication and social

skills for these interactions.

Prognosis

The prognosis for high-functioning children can be confusing

for parents and caregivers. Some researchers report fairly grim statistics

regarding adult adjustment of high-functioning people. Wing (1981), for

example, reports that of 18 people in her study diagnosed with AS:

4 had an affective illness; 4 had become increasingly odd and withdrawn,...1

had psychosis with delusions and hallucinations...1 had an episode of catatonic

stupor; 1 had bizarre behavior and an unconfirmed diagnosis of schizophrenia;

and 2 had bizarre behavior, but no diagnosable psychiatric illness. Two...had

attempted suicide and 1 had talked of doing so. The rest were referred

because of their problems in coping with the demands of adult life. (p.

118)

On the other hand, Szatmari, Bartolucci, Bremner, Bond, & Rich (1989)

offer a more positive prognosis. They state that the results of their work:

indicate that the grim prognosis often given to parents of young autistic

children may not be universally warranted. A small percentage of nonretarded

autistic children (perhaps those with good non-verbal problem-solving skills)

can be expected to recover to a substantial degree. It may take many years

to occur, and the recovery may not always be complete, but substantial

improvement does occur. (p. 224)

Szatmari, Bartolucci, Bremner, Bond, and Rich (1989) provide some details

of the types of families included in their study. They stress that they

cannot prove the relationship between the family characteristics and the

positive prognosis of their subjects; they simply wanted to report the

anecdotal evidence they gathered. They state that the autistic subjects

involved in the study came from middle-to high-income backgrounds. They

typically had parents, specifically, mothers, who were vocal advocates

for services to meet their children's needs. The authors state that the

"parents worked very hard for their autistic children and often made major

sacrifices in terms of their own family lives" (p. 222).

Problems Encountered by People with Asperger's Syndrome

A common problem for people with AS is the expectations that

others have of them. "The more capable an autistic person appears to be,

the more likely it is that he will be expected to manage his own affairs

without supervision (Frith, 1991, p. 195). However, this is not always

possible. People with AS can get confused and frustrated by these normal,

everyday expectations.

Another problem, as described by Wing (1992) deals with society's perceptions

of high-functioning autistic people. One should not misinterpret the social

awkwardness of high-functioning people with AS to mean that they do not

want to have friends. What seems to be happening is "that their lack of

understanding of the subtle rules of social interaction and communication"

(p. 40) prevents them from forming or even initiating a relationship.

Grandin (1992) makes an interesting observation about the family histories

of high-functioning individuals with autism. From her review of the literature

and from talking to several families in which autism occurs, she has found

that "Family histories of high-functioning autistics often contain giftedness,

anxiety or panic disorder, depression, food allergies, and learning disorders"

(p. 113).

Hyperlexia

Definitions and Characteristics

In the past there has been

confusion as to how to define hyperlexia. In 1976, Elliott and Needleman

reported that there was much confusion in the literature regarding the

definition and diagnosis of hyperlexia. However, one characteristic was

clearly evident in the literature; "The unique characteristic of these

children…is their supernormal sensitivity to visual linguistic symbols.

Production of speech sounds…may be non-existent

or severely retarded, but the unusual attraction to written symbols

is common to all" (p. 346). Elliott and Needleman further report that the

literature, up to that time, was also clear about another characteristic

of hyperlexia; "the interest in written language and ability to read simply

'appeared' upon exposure to written material, much as spoken language appears

after exposure, without the necessity for explicit instruction" (p. 348).

Some definitions of hyperlexia have included all children who

read above their comprehension level. Healy (1982) argues that "many school

children exhibit such discrepancies; to label them all hyperlexic would

be to miss the essential features of this unique condition" (p. 334). Healy

reports in her 1982 study that certain critical features must be present

in order to diagnose hyperlexia. These include:

children who spontaneously read words before age 5 despite disordered

linguistic, cognitive, and interpersonal development. An intense and preoccupying

interest in graphic symbols replaces other developmentally appropriate

activities for these children….such children may or may not continue to

develop phenomenal word-calling abilities, although word recognition skills

remain well above expectations based on other cognitive or linguistic abilities.

Comprehension on both listening and reading tasks is impaired. While it

may be present for literal units, it breaks down when abstract or organizational

strategies are required to gain meaning. (p. 334)

S. is a two and a half year old boy with autism. S. began to read

at a very young age. He can read brand names on household products and

common logos found in the community. S. can remember and recite commercials

he hears on the television. S. can match the commercials to the proper

products on the store shelf. He does this by singing or repeating the commercial

while pointing to the product or holding the product in his hand.

Aaron (1989) defines hyperlexia a "a reading disorder caused

by severe deficiencies in comprehension accompanied by extraordinary facility

in decoding that has developed spontaneously and at a very young age" (p.

158). Levy (1988) has developed a similar definition, saying that some

high-functioning individuals with autism may have very advanced reading

skills for their age, but their comprehension does not match their reading

level. Other characteristics of the

hyperlexic include: proficient spelling of a limited number of words; precocious

readers of pseudowords; and, may demonstrate understanding of simple sentences,

however, they do extremely poorly on comprehension tasks of complex sentences,

stories and passages (Aaron, 1989).

Other Characteristics

Children with hyperlexia typically begin to develop language normally,

but then may stop speaking at around age 18 months. Other language deficits

include perceiving language differently than normally developing children.

For example, "they perceive language in phrase chunks rather than in words

or morphemes, and they have difficulty comprehending new utterances as

well as generating new utterances of their own" (Kupperman & Bligh,

p. 1). The utterances of hyperlexic children often contain quoted dialogues

and commercials they have witnessed on television or the radio (Kupperman

& Bligh).

These children may also "have an intense need for order,ritual, and

routine. Many also react strongly to touch, smells, and loud noises" (Moses,

1994, p. 25). They may exhibit non-compliance, anxiety, have difficulty

with transitions and with peer interactions (Kupperman & Bligh).

T. is an eight year old boy with autism. T. could read the test instructions

upside down, while being given a psychological assessment.

Prognosis

The prognosis for hyperlexic children is usually positive.

They often have excellent memories and good imaginations which enable them

to do well in school (Moss, 1994).

Working with children diagnosed with Asperger's Syndrome can be rewarding,

as well as frustrating. Because most children with Asperger's Syndrome

often possess the ability to communicate verbally, the opportunities for

interaction are typically greater than with children who function at the

lower end of the autism continuum. Because children with Asperger's syndrome,

however, usually appear like typical children, many people misinterpret

their abilities and expect normal academic and social functioning of them.

In fact, we know that these children do not always do well academically,

and are often very handicapped socially.

Autism: Relationship to Mental Retardation

Definition

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.)

(1994) defines mental retardation quite simply as comprising of three components.

A person must have a significantly sub-average IQ, show significant impairments

of adaptive behaviours, and present with these two characteristics before

the age of 18. See Appendix C for a more detailed list of the criteria

used in

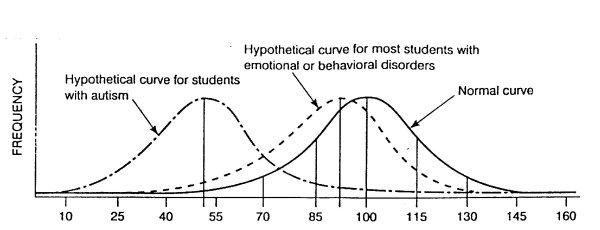

U. is a four year old boy with autism. He knows all the alphabet